Mystical, Mythical, Mysterious Magnum: 357 Atomic

When it comes to sixguns, the 1950s were not just magnificent, they also seem to be magical. In the beginning of the 1950s S&W introduced the first J-Frame, the Chiefs Special and the 1950 Target chambered in both .44 Special and .45 Auto Rim. In 1954, the .357 Highway Patrolman was introduced. It was just a matte finished version of their Bright Blue original .357 Magnum. One year later was the arrival of the first K-Frame Magnum, the .357 Combat Magnum followed in December of that same year by the first .44 Magnum.

Over at Colt we find the introduction of their first .357 Magnum in 1954, followed by the Python one year later. And although Colt had dropped the Single Action Army in 1940 “never to be produced again” it came back as the Second Generation SAA in late 1955.

Bill Ruger arrived on the scene in 1949 with his Standard Model .22 semi-automatic and then brought out an SA .22, the Single-Six in 1953. The first .357 Blackhawk arrived in 1955, followed by the .44 Magnum Blackhawk in 1956. Before the ’50s ended Sturm and Ruger covered both ends of the spectrum with the introduction of the .22 Bearcat and the .44 Magnum Super Blackhawk.

New Kid On The Block

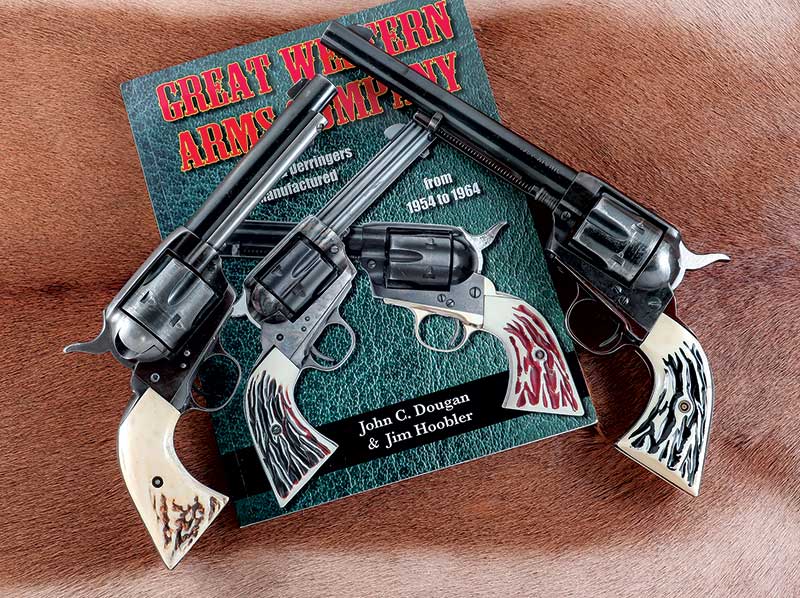

S&W, Colt and Ruger are still producing firearms, of course, however there was another manufacturer arriving in the 1950s. One William Wilson, after receiving word from Colt saying they had no intention of reintroducing the Single Action Army, began producing his Great Western Frontier Model Single-Action in Los Angeles in 1954. Contrary to some beliefs, this was an All-American sixgun produced in America with All-American parts. In early advertising Wilson even used Colt SAs and some Colt parts in the guns. A keen eye can spot the difference between a Great Western and a Colt, but most observers wouldn’t notice the difference, at least until the Great Western was cocked to reveal a Christy Gun Works style upside down “L” shaped hammer to match the frame-mounted firing pin. They show up quite regularly in western movies and TV shows from that time period. Some were also produced with regular Colt hammers.

Great Westerns were produced in the standard Colt SAA barrel lengths of 43/4″, 51/2″, and 71/2″ and the rarer 3″ Sheriff’s Model, Target Model, Buntline Special, and the very rare Deputy Model with a 43/4″ ribbed barrel, and adjustable sights. Standard calibers for the standard production barrel lengths were .22 LR, .38 Special, .44 Special and .45 Colt. The standard grip was a “B-Western” faux plastic stag, however such materials as ivory and pearl were offered at extra cost as was custom engraving. Between the arrival of the Great Western in 1954 and the introduction of the .44 Magnum from S&W and Ruger for the general public in early 1956, Bill Wilson saw the need for a more powerful sixgun than the .357 Magnum. The result was the Great Western .357 Atomic.

Atomic Age

In 1935, the original S&W .357 Magnum with ammunition from Winchester used a 158-grain bullet over 15.4 grains of #2400. Elmer Keith reported at the time, citing this load, the pressure was 46,000 CUP. Current SAAMI Specs for the .357 Magnum is 35,000 psi. The Great Western .357 Atomic increased the powder charge to 16.0 grains, and in the 1956 edition of Gun Digest editor John Amber reported on the .357 Atomic loading of a 150-grain bullet over 16.0 grains of #2400.

Great Western barrels were marked on the left side with “.357 Atomic.” To this day researchers are still trying to find out more about the .357 Atomic cartridge. John Dougan and Jim Hoobler have written an excellent book on the Great Western revolvers, but mysteries still remain. To this date no one has come up with a cartridge head stamped .357 Atomic, nor have any cartridges been found that were longer than the original .357 Magnum.

We have discovered some chambers found in .357 Atomic cylinders will accept cartridges longer than the normal Magnum cartridge case. Does this mean there were longer cartridges available or simply quality control was not the best when chambering the cylinders? If the case was longer, increasing the powder charge by such a small amount probably wouldn’t gain anything.

Early advertising for the .357 Atomic Great Western Frontier Revolver proclaimed: “The most powerful handgun ever made. For the peace officer, big-game hunter, or householder who wants real stopping power and long range. Ballistics from a 71/2″ barrel are 1,660 fps with 906 ft-lbs. muzzle energy. Note: These revolvers have been tested with ammunition generating internal pressures of 52,000 lbs. per square inch without the slightest indication of failure.”

Charge Origins

Where did Great Western get their 16.0 grain powder charge? Remember, this was 1954. Doing a little research in my collection of Lyman Reloading Manuals, I found the 1958 Handbook of Cast Bullets edition listed the 150-grain Thompson HPGC (Hollow Point Gas Check) over 16.0 grains of #2400 for a muzzle velocity of 1,617 fps. This same load is also listed in the 1955 Ideal Handbook #40. They also list 15.5 grains for the 158-grain Thompson GC for 1,538 fps. So, did they get this load from Great Western? Not so fast. We find this load also listed in Ideal Handbook #39 which was published in 1953, one year before Great Western opened their doors. So, the superhot load from Great Western was actually a standard maximum loading found in a reloading handbook before Great Western arrived. Lyman currently lists the 16.0 grain load with the 158-grain GC bullet in the Pistol and Revolver Handgun, but only for use in the Thompson/Center Contender.

Hot Stuff

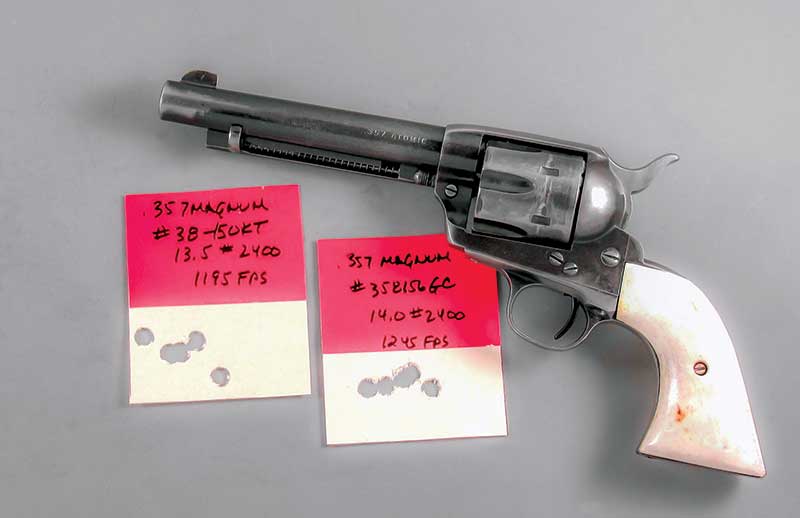

Col. Charles Askins tested one of the very early .357 Atomic sixguns. “Bill Wilson, chief guru at Great Western, contributed a 71/2″ .357 for the cartridge he calls the ‘Atomic’… The first six shots with the Great Western .357 Atomic indicated excessive headspace. Examination of the cartridges, not those provided by Bill Wilson but standard Western Metal Piercing stuff, showed the primers were almost pushed out of the primer pockets. The indentation of the firing pin had been completely ironed out, indelible evidence of excessive headspace. I did not fire the GW after this showing.” This problem was soon corrected and is not exhibited in my pair of .357 Atomic sixguns.

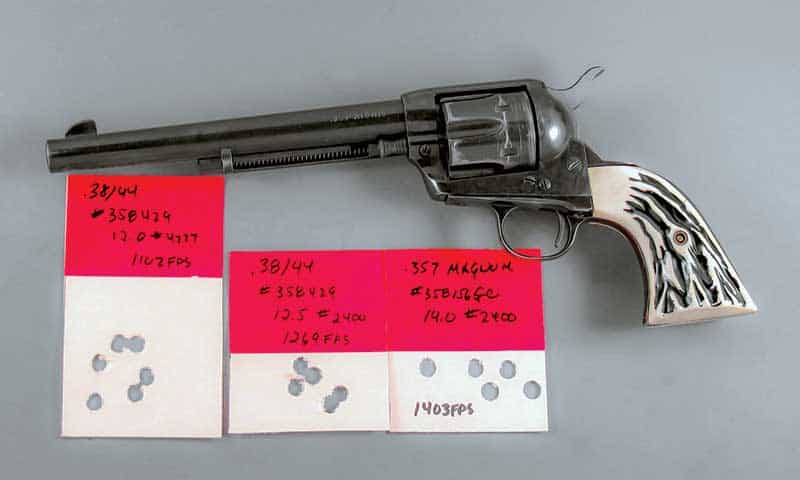

Today’s Alliant #2400 seems to be slightly hotter than the original from Hercules. Both friend Brian Pearce and I have concluded charges should be cut about six percent, which means 15.0 grains is about as high as we should go with today’s powder. For many years I used 15.5 grains of Hercules #2400 with the 158-grain Thompson GC bullet. Now I am older, and so are my sixguns, and I rarely top out over 14.0 grains.

However way back in the 20th century I did do some testing with the 16.0- grain Hercules #2400 under the RCBS #38-150 KT bullet which is very close to the original design from the 1930s by Phil Sharpe used in the Winchester factory loads of the time. Before I publish my results here, I would say do not use this load with current #2400. Highest muzzle velocity from an 8″ Colt Python was 1,638 fps. Others in chronological order were Dan Wesson 10″, 1,585 fps; S&W 83/8″ .357 Magnum, 1,493 fps; 6″ Dan Wesson, 1,418 fps and a 45/8″ Ruger Flat-Top Old Model at 1,402 fps.

Before the doors closed on Great Western in 1964, at least a baker’s dozen calibers had been listed. In addition to the above standard chamberings, others included .22 Magnum, .44 Magnum, .44-40, .38-40, .22 Hornet and .30 Carbine, all of which are extremely rare. Just because the caliber was listed does not mean one can find a Great Western so chambered.

The .357 Atomic lasted about two years and continues to be shrouded in myths and mystery. When one considers the .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum have been around for 85 and 65 years respectfully, and are still surrounded by myths, it isn’t very likely the mystery of the .357 Atomic will ever disappear.